Talking about my mental illness with my child

Many parents wonder if they should talk to their child about their mental illness or their partner’s mental illness. Some of the most frequently asked questions are: What are the benefits of telling my child? How do I prepare myself to address this topic with my child? How do I start the conversation with my child? What should I tell my child? Is my child able to understand?

Are you one of these parents? Are you wondering if you should talk to your child about your mental illness or that of your partner? If you are asking yourself these questions, we invite you to read on.

Why discuss my mental illness with my child?

Most of the time, problems experienced by parents are not explained to their children, since it is often mistakenly thought that this type of information would either be too difficult to explain or would cause them distress. In this sense, many parents feel that it is best to avoid telling their children about their own or their partner’s mental illness in order to protect them.

However, it is important to inform all family members, including children, about a parent’s mental illness, its symptoms and its impact so that everyone can better understand it and feel less anxiety about it. Indeed, when a parent’s issues are not explained to their child, they may have many questions.

Example. Thomas (8 years old) had many questions when his father experienced his first depressive episode:

- “Why is my father like this?

- Why does he stay in bed all weekend?

- Will I become like him?

- Who will take me to school tomorrow?

- What will happen to my father if I don’t stay with him today?”

Imagine you have a lamp that won’t turn on. Could you identify the reasons why it won’t turn on? It may be that :

- there is a power failure

- the lamp is not plugged in

- there is no bulb

In this example, a judgement is made about why the lamp isn’t functioning. This is similar for people who are not “functioning” properly in life. Too often we conclude that they are doing it on purpose, yet there may be many reasons for their behaviour! So, it is normal for children to try to find an explanation for what is happening to their parent.

If children do not have the correct information to understand what is happening, they may develop false beliefs or feel sad, anxious, worried, rejected or even responsible for what is happening. Example: “My mother often cries because I don’t listen to her well enough.”

Children need to be reassured that these emotional reactions are symptoms of the illness (such as coughing when you have a cold) and are not the result of something they have done or said to their parent.

When parents talk openly about their experiences and difficulties, in language that children can understand and that is appropriate for their age and capabilities, children are better able to cope with the situation.

Why talk about it?

There are many benefits to discussing your (or your partner’s) mental illness with your child. In particular, this allows you to :

- Reassure your child and promote a sense of security

- Address your child’s fears and concerns

- Foster trust and respect between family members

- Foster positive and caring family relationships

- Help parents and children understand each other better

- Increase the sense of belonging and mutual support in the family

- Find solutions together to deal with difficult situations

- Foster a sense of hope for positive change

Although it can be difficult for young people to understand their parent’s mental illness, they generally prefer to receive information about it from their parent.

How do I prepare myself to address this topic with my child?

It can be difficult for a parent with a mental illness to talk about their experiences and symptoms with their child. Some don’t know what to say, others wonder how to explain the situation. To begin with, it may be helpful to make sure you understand your mental illness before you try to explain it to your child. When you are able to explain it to yourself in your own words, you will feel better equipped and more confident talking to your child about it, as well as addressing their questions and concerns.

To help you understand your mental illness or get ideas for talking about it with your child, you may want to ask a health care professional questions or consult an outside resource (e.g., a community organization or a book about mental illnesses).

- What topics am I comfortable with and ready to talk about with my child? (e.g., my symptoms)

- What topics would I like to avoid discussing with my child? (e.g., marital disputes)

- What are the topics I would like to discuss with my child but feel uncomfortable discussing at this time?

- Is there any information I would like to know before talking with my child?

How do I start the conversation with my child?

There are several ways to engage your child in this discussion. It can be helpful to think in advance about where and when you would like to discuss your (or your partner’s) mental illness. For example, some parents have chosen to talk to their child at mealtime, during a car ride or after school. The important thing is to start the conversation in a place where everyone will feel comfortable and safe, and where you and your child will not be disturbed or interrupted. It is important that you and your child are ready and willing to have this discussion.

As your child develops, their questions and need for information will change. This may be due to a desire to learn more as they grow older or because they have had new experiences related to the mental illness. So, it may be useful to start with a preliminary discussion that will lead to further conversations over time. You may have to discuss your mental illness with your child on more than one occasion.

During these discussions, it is important for you to be prepared to answer your child’s questions. You can think about what questions they might ask you and how you will answer them. For example, they might ask you: “Why are you always tired? Why does it seem like you’re always getting angry? How did you know you had this illness? Will I have the same illness when I grow up? Are you seeing a psychologist?”

- Get on their level or sit next to them

- Talk about what you are experiencing and how it is affecting you

- Consider your child’s age and capabilities so that they can understand the information you are giving them

- Use simple and concise language

- Use specific examples (e.g., you could compare the mental illness to a physical illness)

- Reassure your child that it’s not their fault that you have a mental illness or that you have certain symptoms

- Invite your child to share their fears and concerns any time they arise, and then be sure to address them

- Explain to your child that you are getting help or have taken steps to get support. They will be happy to know this.

- Let your child know that you are available to answer their questions and that there will be other opportunities for you to discuss this together

- Be sure to listen to what your child has to say in return

Caution : While it is important to talk to your child about your illness, your child should not become your confidant or therapist. Revealing details about your personal life or your concerns is not the aim of this discussion.

If your family rarely talks together, it may take time to feel comfortable doing so, especially during difficult times. The first discussion is often the most difficult and stressful, but it will be the starting point for other conversations that will help your family understand each other better over time.

Will my child be able to understand?

Children’s understanding varies depending on their age, ability and stage of development. As a parent, it can be difficult to think about how your child might perceive the situation and your mental illness.

It can be helpful to try to put yourself in your child’s shoes and think about how they might perceive your mental illness.

- Has my child noticed any changes in my behaviour?

- What symptoms or behaviours has my child noticed?

- What can my child see in my facial expressions?

- What can my child hear in my tone of voice?

- What would my child understand about my symptoms?

- How does my child react to my symptoms or behaviours?

- How might my child feel about my symptoms?

- What symptoms or behaviours do I have that might be concerning to my child?

- What, if anything, did my child understand from my explanations during our discussions? Did I use language appropriate for their age and capabilities?

It is a great idea to do this reflection exercise with someone who knows you well, as they may have observed your symptoms from a different perspective. They may also be able to help you identify how the mental illness will impact your family and your role as a parent.

What does my baby understand?

As a parent, it can be very difficult to think about how your baby might perceive your mental illness. Changes in your behaviour, facial expressions and tone of voice are things your baby will notice. Babies may not be able to understand language, but they can easily sense and respond to your emotions and tone of voice. Often you may find that when your emotions and behaviour change, your child’s reactions change as well. So, it can be helpful to think about how the symptoms you are experiencing may be experienced by your child. For example, what can your baby see? What can they hear?

While it is not necessary to explain the mental illness to your baby, it is important to find ways to meet their emotional needs. This way, your child will feel loved, safe, supported and happy.

- Smile at your baby when they look at you or make noises

- Hug, kiss or tickle them

- Sing songs or read a book to your baby

- Repeat the sounds your child makes to create a conversation with them

- Carry your baby close to you and rock them gently

- Use a calm, gentle voice when talking to your baby (e.g., when they seem upset or sad)

What does my preschooler understand?

Like infants, toddlers and preschoolers use tone of voice and body language, including their parents’ facial expressions and gestures, along with their growing understanding of language to make sense of their experiences. So, it is helpful to take some time to think about how the symptoms of your mental illness may be affecting these areas, especially when you are going through a difficult time. Young children are very alert to their surroundings and can detect even the smallest changes in their parent’s behaviour, even if the parent tries to hide them.

- Young children use their behaviour and emotions to communicate (e.g., to express their frustrations or seek attention)

- Your child needs to be reassured that you are able to meet their needs in a calm and positive manner, even in difficult times

- We suggest you set aside time each day to spend quality time with your child , such as reading a story, listening to music or playing ball.

When you talk regularly with your young child, even in difficult times, it helps strengthen your emotional connection with them.

Here’s an example of how to start a discussion with your child about the mental illness. “I am sick, that’s why I am very tired and sleep a lot. I don’t like to feel that way. I love spending time with you. We can do a quiet activity together tomorrow when I feel better.”

“I’m cranky or angry right now. It’s not you that makes me angry and I’m not angry at you, it’s because I’m sick. This is how my illness makes me feel. It’s not your fault. I can see that this makes you sad. I will try to be more mindful of your feelings.”

What does my elementary school-aged child understand?

Small or large changes in your behaviour or body language can be noticed by elementary school children, even if you try to hide them. At this age, children often believe that they are somehow responsible for their parents’ behaviour. They may also feel responsible for their parents’ well-being and recovery. When your child doesn’t understand what’s going on, they may worry (e.g., about you, your health or your safety), feel alone or think they are responsible. It’s a good idea to talk to your child about your (or your partner’s) mental illness and help them understand what’s going on.

Here is an example of how to start a discussion with your child about your mental illness

“You may have noticed that I’ve been acting differently or strangely lately. You’ve probably noticed that I’ve been sleeping a lot, that I’ve been crankier or moodier and that I’ve been spending less time with you than usual, such as helping you with your homework or playing. I want you to know that it’s not your fault, it’s because of my mental illness.“

“Are there any changes you’ve noticed in me that concern you? I have what is called a mental illness. It’s not your fault that I have this illness! It makes me very tired so that I have no energy to do activities or go to work, and I am angry or irritable more often. Let me know if you have any questions or if you are worried, we can talk about it together. I want to help you understand what’s going on. If you want, you can also talk to Grandma or Grandpa, or another adult.“

Some practical tips

- Explain to your child that it’s okay to talk about mental health issues. It’s not a taboo subject!

- Take a moment to pause after each new piece of information to allow your child time to absorb the information, think about what you are saying and ask questions. A period of reflection may be necessary to bring out questions in your child

- If your child asks you a question that you don’t know the answer to, offer to find the information together or mention that you’ll get back to them with the answer later

- If you are not able to answer their questions, refer your child to their support network (e.g., a family member, friend or professional) so that they can ask questions of someone they trust

- If you are not feeling well or have no energy, explain to your child that you can talk at another time or refer them to their support network

- Encourage your child to seek support from you or other trusted individuals, for example, when they feel worried or overwhelmed

What does my teenager understand?

As a parent, it can be difficult to get a sense of how your teenager feels about the situation, since young people at this age often don’t communicate their feelings very well. Teenagers develop a more complex view of their environment and the world around them. They are trying to find meaning in their relationships with others, including their parents.

Teens tend to worry about their parents and the impact of the mental illness on family relationships. As your teenager progresses cognitively, they may have questions about various aspects of your mental illness. They may want to know how you were diagnosed, your symptoms, your treatment plan and whether they could develop the same illness as you. Your teen may also be wondering how they can explain the situation to peers without betraying you.

The conversations you have with your teen about your (or your partner’s) mental illness are important. Teens have developed the ability to understand the point of view of others and their capacity for introspection. These discussions can help your teen better understand their experience and yours, as well as get answers to questions and concerns. This will be very helpful for them! You will also be able to put your own experience into words, as well as learn about your teen’s perspective and experiences. Conversely, when your teenager doesn’t understand your behaviour or what’s going on, they may experience negative emotions (e.g., guilt, sadness, anger, worry and isolation).

- What impact do my symptoms or behaviour have on my teenager?

- How are my symptoms or behaviour affecting my relationship with my teenager?

- In what ways does the situation impact my teen’s involvement in leisure activities or social relationships (e.g., bullying and less time spent with friends)?

- What behaviours or symptoms might be more difficult for my teenager to experience?

- What concerns might my teen have about their own mental health?

- In what ways might my symptoms and behaviours impact my teen’s day-to-day functioning?

- What information should I give my teenager to help them understand what they may have observed, heard or seen in my behaviour?

Here is an example of how to start a discussion with your child about your mental illness

“You may be worried because you have noticed that I have been very sad, tired, irritable and low on energy lately. You may have trouble understanding what is going on! Have you noticed any changes in my behaviour? It’s important for you to know that it’s not your fault. In fact, I have been diagnosed with a mental illness called depressive disorder. That’s why I have been acting differently than usual. It’s because of the symptoms of my illness. I’m here for you if you want to talk about it, if you have any questions or if you’re worried. You can also talk to Grandma or Grandpa if you feel the need. They already know about the situation. Is there anything you would like to know about my illness?“

Some useful tips

- Keep in mind that teens have access to a lot of information from many different sources (e.g., from peers, television, social media or websites). These are not always good sources of information, or the information may be different from what you experience. Refer them to reliable online tools

- Debunk any myths and misinformation your teen has received

- Normalize talking about mental illnesses. They are not a taboo subject!

- Invite your teen to ask questions or express concerns when they arise. Some will need time to assimilate and understand the information. Questions may not arise until later

- Be open to discussion so that your teen feels comfortable and safe enough to ask questions and express their feelings, even the difficult ones, at any time

- Tell your teen about your symptoms and you treatment or strategies for getting better

- Some teens will feel more comfortable discussing this topic while doing something else. For example, it may be easier to start a conversation during a walk together or when you’re driving them to school

- Encourage your teen to seek support from you or other trusted individuals (e.g., friends and extended family) when they are experiencing negative emotions, feeling worried or overwhelmed or have questions about mental health, for example.

Read the When your Parent Has a Mental Illness guide, which provides information and advice for youth who have a parent with a mental illness. It can help you understand what teenagers and young people who are transitioning toward adulthood and have a parent with a mental illness may be experiencing.

Reflection exercises

My symptoms from my child’s perspective

Before starting the discussion with your child about your mental illness, we suggest identifying the symptoms you are most concerned about because of their impact on your role as a parent. Then, you can take some time to think about how your child may perceive these symptoms.

My strengths as a parent!

We now suggest identifying the characteristics that you are most proud of or those that your child appreciates most about you. Then, you can reflect on how your child perceives your strengths or examples from everyday life where these have been helpful to you in your parenting.

It is important to recognize your strengths, as they can help you better face challenges and deal more positively with the stresses of everyday life. You will be able to take advantage of your personal and family strengths during difficult times.

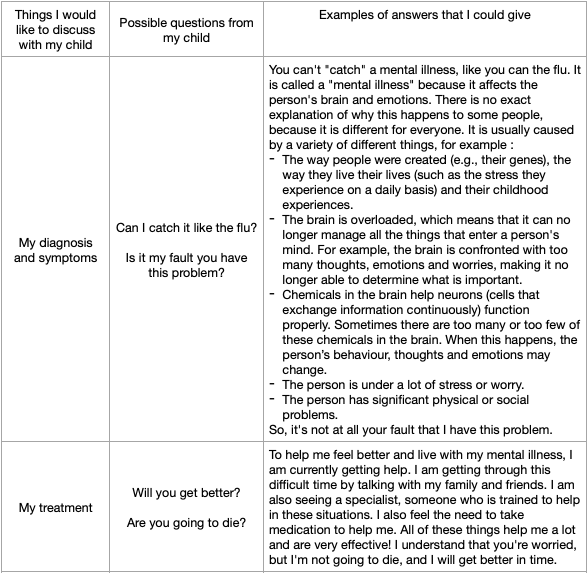

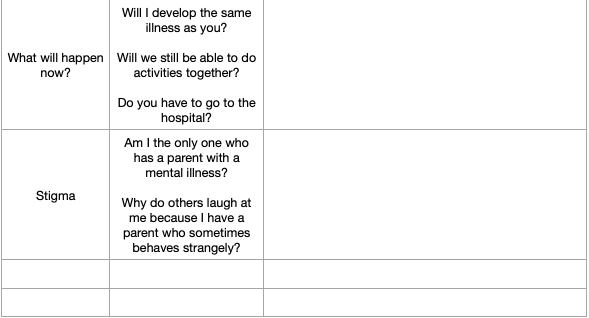

How can I answer my child’s questions?

To prepare you to discuss your (or your partner’s) mental illness with your child, we have provided a reflection exercise on the aspects you would like to discuss with your child, the questions that your child might have during your conversation and how you might respond. Examples are also provided to guide your thinking.

Remember to adapt your language to your child’s age and capabilities!

Preparing for a discussion with my child

In this fact sheet, you have been provided with different tips and examples for talking about your mental illness with your child. We now suggest writing your own discussion script to prepare for a conversation with your child.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Exercises adapted from “Talking about mental illness with your child” and “Thinking about questions and answers” from The Children of Parents with a Mental Illness national initiative, 2016.

A big thank you to Stephanie and Adela, parent members of the LaPProche advisory committee, for their collaboration and involvement in the designing of this fact sheet.

This content was developed at the Université du Québec en Outaouais by the Research and action laboratory for people with mental health problems and their loved ones (LaPProche) with funding from the Fonds des services aux collectivités (FSC2018-013) of the Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur and in collaboration with CAP santé mentale.

The information contained in this sheet does not replace seeking professional advice. If you have any questions or concerns, please see a professional.

References

Beardslee, W.R., Martin, J., & Gladstone, T. (2012) Family Talk preventive intervention manual. Boston Children’s hospital: FAMPOD. https://fampod.org/

Cooklin, A. (2013). Promoting children’s resilience to parental mental illness: engaging the child’s thinking. Advances in psychiatric treatment, 19, 229-240. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.111.009050

Christiansen, H., Anding, J., Schrott, B., & Rohrle, B. (2015). Children of mentally ill parent – a pilot study of a group intervention program. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(1494). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01494

Lamy, C. (2018). Il pleut à la maison : Parler de votre santé mentale avec vos enfants. Éditions de Mortagne.

Piché, G., Villatte, A., & Habib, R. (2019). Programme FAMILLE+. Manuel du parent [document inédit]. Université du Québec en Outaouais : Laboratoire de recherche et d’actions pour les personnes ayant des problèmes de santé mentale et leurs proches (LaPProche).

Piché, G., Villatte, A., Habib, R., & Vetri, K. (2019). Programme FAMILLE+. Manuel de l’enfant [document inédit]. Université du Québec en Outaouais : Laboratoire de recherche et d’actions pour les personnes ayant des problèmes de santé mentale et leurs proches (LaPProche).

Reupert, A., Cuff, R., & Maybery, D. (2015). Helping children understand their parent’s mental illness. Dans A. Reupert, D. Maybery, J. Nicholson, M Gopfert, & M. Seeman (dir). Parental psychiatric disordor: Distressed parents and their families. Cambridge University Press.

Solantaus, T., & Ringbom, A. (2002). How Can I Help My Children: A Guide Book for Parents With Mental Health Problems.

The Children of Parents with a Mental Illness national initiative. (2016). Starting the conversation. http://www.copmi.net.au/parents/helping-my-child-and-family/talking-about-mentalillness/starting-the-conversation

The Children of Parents with a Mental Illness national initiative. (2016). Talking about mental illness with your child. http://www.copmi.net.au/parents/helping-my-child-and-family/talking-about mental-illness

The Children of Parents with a Mental Illness national initiative. (2016). Communicating with babies. http://www.copmi.net.au/parents/helping-my-child-and-family/talking-about-mental illness/babies

The Children of Parents with a Mental Illness national initiative. (2016). Talking to toddlers and pre schoolers.http://www.copmi.net.au/parents/helping-my-child-and-family/talking-about mental-illness/talking-to-toddlers

The Children of Parents with a Mental Illness national initiative. (2016). Talking to primary school age children about parental mental illness. http://www.copmi.net.au/parents/helping-mychild-and-family/talking-about-mental-illness/talking-to-primary-school-children

The Children of Parents with a Mental Illness national initiative. (2016). Talking to teenagers about parental mental illness. http://www.copmi.net.au/parents/helping-my-child-and-family/talkingabout-mental-illness/talking-to-teenagers

The Children of Parents with a Mental Illness national initiative. (2016). Thinking about questions and answers. http://www.copmi.net.au/images/pdf/Parents-Families/Qus-answers.pdf

The Children of Parents with a Mental Illness national initiative. (2016). Talking about mental illness with children of primary school age – information sheet. http://www.copmi.net.au/images/Resources/Thumbs/Primary-school-aged-children_Talking factsheet-final.pdf

Villatte, A., Piché, G., & Habib, R. (2020). Quand ton parent a un trouble mental. Conseils et témoignages de jeunes. Université du Québec en Outaouais : Laboratoire de recherche et d’actions pour les personnes ayant des problèmes de santé mentale et leurs proches (LaPProche).

Wendland, J., Boujut, É., & Saïas, T. (2017). La parentalité à l’épreuve de la maladie ou du handicap : quel impact pour les enfants? Champ social.

To cite this document, please provide the following reference: LaPProche Laboratory. (2021). Talking About Mental Illness with Your Child. Université du Québec en Outaouais.

© LaPProche 2021| lapproche.uqo.ca

All rights reserved.

Any reproduction in whole or in part by any means whatsoever is prohibited without the written permission of LaPProche.